Why AI Will Need a Ledger Before It Thinks Again

Far from being about a James Bond movie, this is pertaining to a very hot topic for those who are following the AI industry development and especially about business models.

To get started, let us go back to about 18 months ago, when I first got introduced to Thomas Malone in a virtual classroom at MIT more precisely, AI: Implications for Business Strategy.

It was one of those “AI for Business” courses that could have easily turned into a buzzword graveyard. Instead, Malone kept—calm, rigorous, almost deceptively gentle—and started talking about collective intelligence. Not AI as a replacement for people, but as a new way of organizing how humans and machines think together.

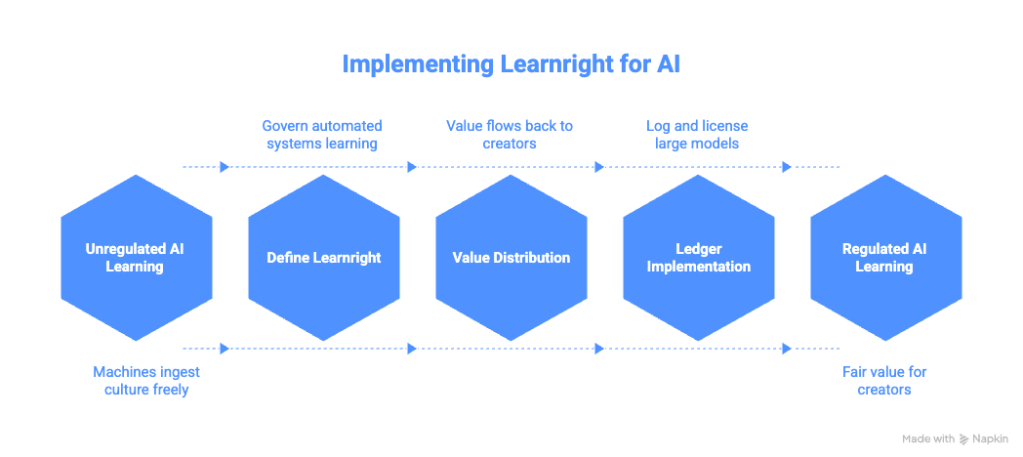

That framing stayed with me. So when I saw his recent argument for a new category of law—“learnright”, a cousin of copyright that governs what automated systems are allowed to learn from us—it felt like a natural extension of the same philosophy. Malone is, as usual, on point: if machines are going to ingest human culture at planetary scale, there should be rules for how that happens and how value flows back to creators.

But it feels there’s a missing chapter in his proposal.

Learnright is a powerful idea. It’s also almost impossible to enforce unless we fundamentally change how we build, log, and license large language models. And that’s where things get uncomfortable—for AI companies, for regulators, and for anyone whose work is already quietly feeding the machine.

Malone’s Learnright Idea, in One Breath

Malone’s argument is deceptively simple: copyright law protects copying; it says almost nothing about learning.

Now, we, humans, are allowed to read Shakespeare, internalize him, and then write something new—as long as we’re not plagiarizing lines. That’s good for society, right?

On the same token (pun intended), Generative AI, however, is not one human reading one book. It’s a cluster of GPUs inhaling billions of pages of text and images, compressing them into patterns, and then generating outputs that compete directly with the people who made the originals.

So before this interesting situation, Malone proposes a new approach, learnright law:

- Copyright → governs the right to copy expressions.

- Learnright → would govern the right to let machines learn from those expressions.

Under learnright, AI companies would need permission (and pay) to use copyrighted material for training. Either all copyrighted material gets automatic learnright protection, or creators explicitly tag their work with learnright notices—like a new kind of “all rights reserved.”

It’s a clean, elegant proposal. It aligns incentives. It acknowledges that generative AI is now big enough, and weird enough, to demand its own legal category.

And yet: there’s a brutal implementation problem sitting right underneath it, no?

The Blind Spot:

You Can’t Regulate What You Can’t Inspect

Learnright assumes we can answer a basic question:

What, exactly, was this model trained on?

With today’s AI, that’s not a question. It’s a fantasy.

Training a large model is not like filling a database. You don’t have rows of “document → author → URL → used on batch 37.” You have:

- Text and images turned into tokens

- Tokens turned into vectors

- Vectors turned into gradients

- Gradients turned into billions of floating-point weights

And for sure that gets much more complicated if explained in technical terms.

Anyhow, once training is done, the model doesn’t “contain” the original texts, images, or their metadata. It contains compressed patterns. It has no idea which pattern came from which book, article, dataset, artist, or journalist, see where I am going with this?

It’s a smoothie. You can taste the banana, but you can’t pull it back out.

Even when models do memorize and regurgitate things verbatim—a known problem—that memory is untagged. If it spits out a sentence from a New York Times article, you can detect the overlap by searching the web. But the model itself cannot say:

“This came from X, scraped on Y, used in training run Z.”

That’s the core enforcement problem for learnright. Creators can’t see inside the model. Regulators can’t either. There is no built-in audit trail.

And that means a company can say “we didn’t train on your stuff,” and there’s no practical, technical way to prove otherwise.

Retrieval Can Cite Sources. Training Can’t.

You might reasonably ask: But wait, what about Delphi.ai, Perplexity, chatgpt, all those systems that happily show sources?

That’s the trick: they’re not citing training data. They’re citing retrieved documents; Stored data that compose Knowledge bases or search queries bringing URLs from search engines or other repositories.

These systems bolt a search engine or vector database onto a language model. When you ask a question, they:

- Search across a live corpus (web, news, proprietary KB).

- Pull back documents—with URLs, names, metadata.

- Ask the LLM to summarize or synthesize those.

- Present you the answer and the sources.

This is called retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and it makes things look transparent. But all the provenance lives in the retriever, not in the model.

Training is different. It’s a one-way, lossy process and Learnright is trying to regulate the training phase. The phase with zero transparency by design.

That’s the blind spot.

The Money at Stake: Trillions vs. Ghost Inputs

This isn’t a niche problem. It’s an economic knife fight.

- The global generative AI market was worth around $16.9 billion in 2024, and is projected to reach about $109 billion by 2030. (grandviewresearch.com)

- The broader AI market is even bigger—roughly $244 billion in 2025, on track to hit $827 billion by 2030. (cargoson.com)

- The global creative industries—the people whose work trains these models—are worth roughly $3 trillion, employing close to 50 million people worldwide. (IFC)

- Training a top-tier model like GPT-4 reportedly cost over $100 million, with estimates putting the compute alone in the $40–$80 million range. (CUDO Compute)

Now add the hypothetical layer:

- If even 5–10% of the creative industries’ output becomes significantly undercut by AI systems trained on their work without compensation, we’re talking about hundreds of billions of dollars in potential revenue distortion over a decade.

- If compliance with a learnright-like regime added, say, 1–3% to AI companies’ operating costs—the range many firms already spend on regulatory compliance today (drata.com)—we’re looking at billions per year in new governance infrastructure, audits, and licensing fees.

(Hypothetical: these percentages are scenario estimates, not current law.)

In other words: this isn’t just a moral question. It’s a giant, unpriced externality in a sector that could add trillions in productivity value. (McKinsey & Company)

And by the looks of things, we’re currently running it on ghost inputs, with no receipts more or less.

The Provocative Fix: License the Right to Learn

So, here is an idea, a provocation , perhaps, if you can’t enforce learnright by peeking inside models, you may have to move the control point.

That’s where the uncomfortable part comes in:

We may need to license the right to operate powerful AI models in the first place?

We already do this in other high-impact sectors:

- Banks and brokers need licenses.

- Airlines and drug companies operate under heavy reporting mandates.

- Public companies spend millions every year complying with financial transparency rules like Sarbanes–Oxley. (zluri.com)

The pattern is simple: when an industry becomes systemic—too big to fail quietly—we don’t trust it to self-report. We regulate it, hard.

For AI, that likely means:

- Licenses for general-purpose AI models above a certain scale.

- Mandatory logging of all training datasets.

- Technically verifiable documentation of data sources and licenses.

- Auditable compliance with copyright and future learnright rules.

The EU AI Act already tiptoes in this direction. It imposes transparency and documentation requirements on “general-purpose AI” models, including expectations around training data and copyright compliance. (digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu) It’s not yet learnright, but it’s a blueprint: if you build a big model, you owe the public an explanation of what went into it.

A full learnright regime would go further: you owe the people whose work trained it, too.

Why a Blockchain-Style Ledger

(Probably) Has to Exist

Say “blockchain” and half the room rolls its eyes. Fair.

But forget token speculation for a second and focus on the underlying idea: an append-only, tamper-evident log of everything that gets added to a system.

If we’re serious about learnright, some kind of cryptographic training ledger becomes almost unavoidable:

- Every dataset used for training gets hashed.

- Its source, license, and timestamp are recorded.

- The record is written to an append-only log—using blockchain, Merkle trees, or similar primitives.

- That log is auditable by regulators and, in some form, by creators.

This doesn’t magically solve attribution. It doesn’t tell you how much influence a particular creator had on a model’s behavior. But it does answer the baseline question:

“Was my work included in this training run?”

That alone would be revolutionary.

Of course, this comes with some hypothetical costs:

- Building and operating global-scale provenance logs and compliance systems could easily run into hundreds of millions of dollars annually for the largest AI companies—comparable to what heavily regulated industries already spend on compliance.

- But non-compliance could be even more expensive, if penalties followed the GDPR model, where major data protection violations can reach up to 4% of global turnover and average fines are now in the multimillion-euro range. (usercentrics.com)

The ledger idea isn’t a silver bullet. It’s infrastructure. It gives learnright something to grip.

Musixmatch for Models: The Broker Layer

Even with a ledger, most creators aren’t going to negotiate directly with OpenAI, Anthropic, or whoever’s next.

This is where your Musixmatch analogy comes in.

In music, Musixmatch sits between lyrics owners and platforms, brokering licenses and distributing revenue. Now imagine a similar data-rights clearinghouse for AI:

- Writers, artists, photographers, coders register their works.

- The clearinghouse hashes and fingerprints the content.

- AI developers license access to the pool for training.

- Usage is logged into the training ledger.

- Revenue flows back to creators through collective licensing schemes.

It wouldn’t be perfect. It would skew toward big rights-holders. It would leave gaps. Recurrence for instance, but it’s at least a recognizable business model. It transforms learnright from a legal thought experiment into an actual market.

And, of course, there’s the darker side: creators trying to catch cheaters.

The “Fake Pill” Tactic: Forensic Traps in the Data

One slightly wicked and / or perhaps naive idea I’ve heard from creators goes like this:

“What if I embed fake pills of content in my work—plausible but false details, or clearly doctored facts—and then later test whether an AI model has learned them?”

If you ask a model a very specific, obscure question that only appears in that doctored content, and it confidently answers with your fake pill, you’ve got circumstantial evidence that your work was in the training data.

Think of it as forensic watermarking at the semantic level.

There are problems, of course:

- AI labs could detect and filter trap content.

- Models might generalize or distort the pill so much it’s no longer a clear smoking gun.

- Courts might treat it as clever but insufficient proof.

Still, fake pills point to where this fight is headed: creators will get more adversarial. They will poke and probe these black-box systems, looking for signs of unlicensed training. If learnright isn’t backed by real transparency, it will be enforced through gotcha moments and public shaming.

That’s not a stable equilibrium. It’s an arms race.

The Geopolitics of Licensed Intelligence

Now let us switch gears and zoom out.

Even if one country—or bloc, like the EU—requires AI licenses, training ledgers, and learnright compliance, others won’t. Models can be trained offshore. Open-weights systems can be fine-tuned anywhere. Enforcement becomes a jurisdictional game.

The only lever that really works in that world is deployment:

- If you deploy your model in our market, you comply with our transparency rules.

- If you sell inference here, you show us your training ledger.

- If you refuse, your model doesn’t ship, or your fines go exponential.

We already see early versions of this logic in the EU AI Act. We saw it with GDPR. It’s messy and uneven, but over time, big markets tend to export their rules.

AI will be no different. The question is not whether it will be regulated. It’s whose regulatory philosophy wins.

Learnright, plus licensing, plus ledgers, is one possible philosophy. There will be others.

Back to Malone—and the Recipe Still in Progress

When I sat in Malone’s class at MIT, what struck me wasn’t that he was optimistic about technology. It’s that he was precise about how humans and machines would need to collaborate if this was going to go well.

His learnright proposal has that same precision. It names something that is currently invisible: the right not just to be copied, but to be learned from.

What I’ve tried to do here is extend his idea into the messy, infrastructural layer underneath:

- Licenses for powerful AI systems

- Cryptographic training ledgers for provenance

- Broker platforms that aggregate creator rights, Musixmatch-style

- Forensic traps and fake pills as a last-resort detection tool

Most likely, none of these is the final solution. My aim is that they become new ingredients in a recipe that is still very much under development.

We’re still figuring out what it means to live in a world where machines can learn from almost everything humans have ever made, and then remake it, at scale, in seconds.

So I’ll end with an invitation.

If we agree that AI shouldn’t have a free, secret pass to learn from everyone, all the time, then the next question is not just how do we stop it, but:

What else do we need to build—legally, technically, economically—to make that learning fair, transparent, and human-centered?

Chip in! What’s your ingredient?

You must be logged in to post a comment.